Island Bay’s cycleway is a fascinating community engagement case study. For five years, the Wellington City Council has been wading through conflict over the new Island Bay cycleway.

We haven’t been involved in the project, but have been watching from a distance as Wellington City Council is a long-standing client for several other business community projects. And recently the High Court released a judgment ruling that the Council’s decision-making and consultation processes were lawful.

It’s an interesting case study for two reasons.

Firstly, there’s the facts. We’ve outlined them below and they underline how vital it is to commit to engagement.

Secondly, there’s the Court’s ruling. The High Court makes some valuable observations about consultation that will be valuable for any council - or for any decision-maker whose decisions impact many people in the community.

We’ve picked out five lessons from the ruling:

Consultation is not a binding referendum

Short timeframes for consultation can be appropriate but only if…

Cycleways are contentious

You need to convince people’s hearts, not just their minds

Low-tech cycleways might no longer be a viable solution.

But first...

What’s happened in Island Bay?

Development of a new cycleway

For those who don’t know the story, here’s a summary based on the High Court judgment.

Back in 2013, there was already a cycleway along Island Bay Parade. I cycled the old cycleway a few times when I lived in Wellington. Cycleway experts would have called it a “low-tech roadside” cycleway. Just a few white lines on the edge of the road.

In 2013, the Wellington City Council started developing a proposal for a new cycleway. The original proposal was for a kerb-side cycleway that would require shifting some carparks further onto the road.

The Council consulted on this proposal and only had 66 written responses from Island Bay residents. For anybody who worked in local government, you’ll know this is a pretty standard response rate for a suburb. Less than 1%. Most of those submissions were in favour.

The Council further developed the proposal and consulted Island Bay residents again. 568 residents responded and this time 57% were against the proposal.

Despite this, work on the new kerb-side cycleway began in September 2015 and was completed by February 2016.

Community members mobilise against the cycleway

The new cycleway was not popular with a number of Island Bay residents and business people. And they started to mobilise.

They formed the Island Bay Residents Association and surveyed approximately 2,000 residents in January 2016 (before the cycleway was finished). 80% said they would prefer a roadside cycleway rather than the kerbside cycleway that was being built.

Then the New Zealand Transport Agency commissioned an independent report. This confirmed the Island Bay community’s view that the new cycleway was a poor solution delivered without proper community engagement. In addition, the Council had under-resourced the communications and engagement for the project.

“Love the Bay” process begins

The Council worked hard to turn things around. They formed a new steering group that had two members from the Island Bay Residents Association, two from Cycle Aware Wellington and one Council rep.

This group helped to launch a new campaign called “Love the Bay”. There was a website to support this engagement, a drop-in shop in Island Bay, and a series of workshops.

IBRA's Vicki Greco and Jane Byrne shaking hands with then Deputy Mayor Justin Lester, Councillor Paul Eagle and Cycle Aware Wellington's Ron Beernink at the start of the Love the Bay process .

Image from DAVID WHITE/ FAIRFAX NZ via http://www.islandbaycycleway.org.nz/blog/why-i-support-the-judicial-review.

The Council then provided all the engagement outcomes to an engineering firm, Tonkin + Taylor. Their task was to prepare some options that reflected the community’s objectives and views. And Tonkin + Taylor read every one of the 2,400 pieces of community feedback to develop the options.

Once again, the Council went back out to the Island Bay community. This time they were consulting on four options prepared by Tonkin + Taylor. The timeframe for this consultation was 14 days.

The Council released the consultation documents on the morning of 31 July 2017.

But then things got even messier

The Residents Association organised a public meeting for that evening. At that meeting, they suggested a fifth option. This was to be called “Option E”.

In the following days, Council staff did what they could to include Option E in the consultation. They were able to change the online survey, so that was pretty simple. But for the paper survey, they instead had to get the word out that people could add a comment to their response to show that they favoured Option E.

And of course most of the responses favoured that additional Option E.

The Mayor then jumped in with another option. This was billed as a compromise option based on some of the community’s feedback.

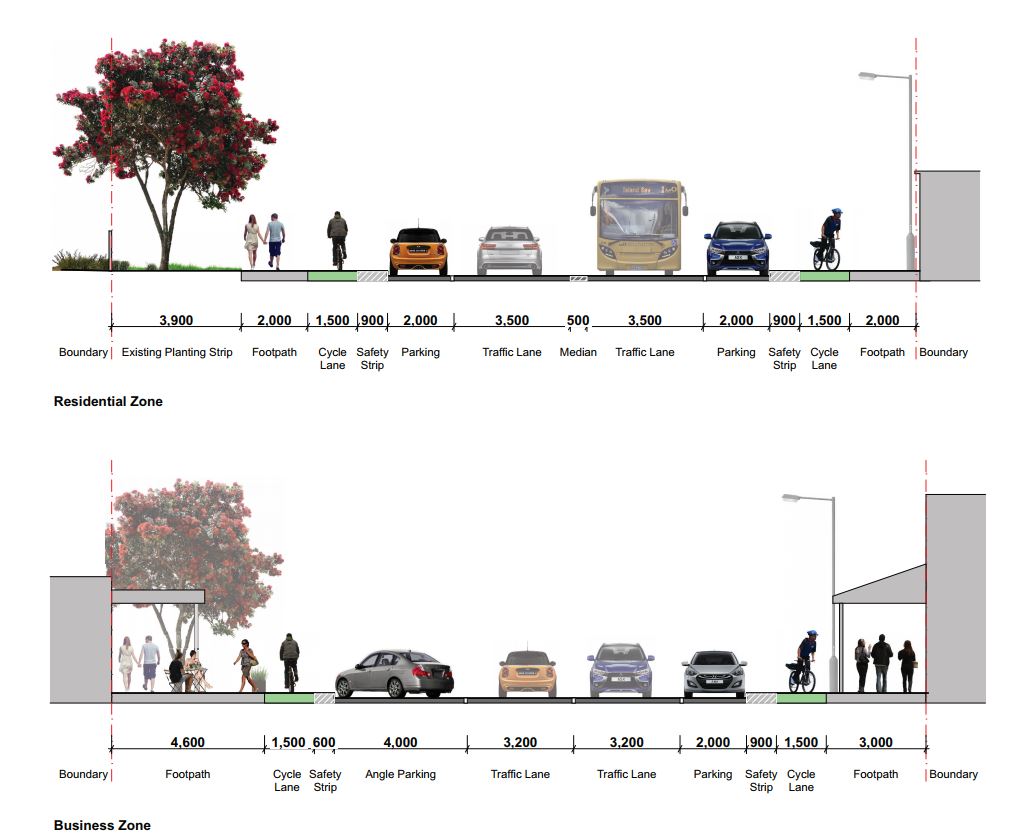

Cross-section showing the Mayor’s Option, via http://www.islandbaycycleway.org.nz/blog/compromise-solution-proposed

Eventually, the Council decided on an option that combined parts of Option C and Option D.

The Association files a judicial review

The Island Bay Residents Association were not happy with the decision. So they filed a judicial review in the High Court to challenge the Council’s decision-making and consultation processes.

The Island Bay Residents Association threw the book at the Wellington City Council, so to speak. They claimed that the Council had breached the Local Government Act’s consultation and decision-making requirements. They also claimed under several other sources of law, such as the principle of natural justice. But the Court mainly just considered the claim under the Local Government Act.

The thing with judicial reviews is the High Court is only ruling on the process, not the actual decision. And that’s why it provides some valuable lessons for community engagement - both for cycleways and more generally.

Five community engagement lessons

Lesson #1: Consultation is not a referendum

One of the Association’s claims was that the Council should have followed the majority’s opinion and gone with Option 5.

The Court tossed that idea to the pavement.

The number of Island Bay residents who responded was 1,991, which is about half of the total respondents and about a quarter of the population of Island Bay. That’s a high turnout rate, so I can empathise with the Association’s argument that it’s as good as a referendum.

The Court made it clear that consultation is not binding on the Council.

Why not?

Because the Council had to consider many information sources, not just the views of the community. They also had to consider the many expert reports provided to them, as well as many other factors beyond just the immediate views of Island Bay residents.

Lesson #2: Short timeframes for consultation can be appropriate but only if...

The Association claimed that the 14 day timeframe for consultation on Options A-D was inadequate.

The Court disagreed. Mainly because there had been 14 months of consultation and engagement in the lead-up to that 14 day period. It wasn’t like the Island Bay community was coming to the issue cold.

“The ultimate measure of whether or not the consultation was meaningful must be what the outcome actually was.” [para 106]

And the outcome was 3,763 formal and 94 informal submissions. Most councils would be impressed with that kind of response. Councils usually get under 100 submission on their Long Term Plans and Annual Plans.

In other words, the 14 day timeframe was adequate but only because of all the other engagement, consultation and communication over the past 14 months.

Lesson #3: Cycleways are contentious

Wellington City Council is not alone in experiencing community conflict over a cycleway. The legal decision mentions the challenges seen in Dunedin. And we’ve written about Nelson’s experience in this article on engagement for infrastructure development.

Cycleways attract conflict because people feel they unfairly favour cyclists over other road users.

I was interested to see the Court referring to the “rights” that vehicle drivers currently enjoy on most roads.

“The implementation of such highly engineered cycleway solutions inevitably involves some compromise to the rights that other road users have previously been able to enjoy...“

In most people’s living memory, we’ve designed roads solely for vehicles. And so we’ve come to believe we have a “right” to an uninterrupted stretch of tarmac to get us swiftly from A to B in our car, truck or van.

But is this really a “right” or is it a privilege?

Perhaps our expectations of a “right” to drive everywhere will change over time, but right now that expectation shapes cycleways into a contentious issue of “cyclists versus the rest”.

It means that you simply cannot send in your B-Team for engagement on cycleways. And once you’ve got the A-Team in place, you cannot risk the project by under-resourcing them.

Lesson #4: You need to convince people’s hearts, not just their minds

Infrastructure change is not just about bricks and mortar. You also need to change people’s behaviour.

Let’s apply that to the cycleways example. When you create a dedicated cycleway, you’re encouraging unconfident cyclists to start commuting. And you’re asking vehicle drivers to behave differently on a road where they previously had the privilege of being the main road user.

When you’re in the business of changing behaviour, you need to work with people’s hearts as well as their minds.

We often see organisations focusing on the investment case for infrastructure and services, and of course that’s crucial. But people don’t just need to be convinced of the benefits of your proposal. They also need to feel positive about the new solution.

Facts and figures are essential but don’t cater to people’s hearts. If you approach your consultation or engagement with an expert mindset, people will rebel. Nobody likes to feel talked-down-to by officials with all the answers.

The Island Bay situation highlights what we call a “public interest gap”. This happens where a decision-maker assumes the public interest in a decision will be low… but it turns out to be high.

In Island Bay, the community wanted more power than the Council initially anticipated - resulting in conflict.

When there is a high public interest, people are less likely to accept an outcome they don’t agree with. If your process isn’t water-tight, they will blame the process as a way to attack the outcome.

That seems to be what happened in Island Bay - causing the process to drag out many years longer than initially anticipated.

So, what’s the takeaway?

Make sure you spend time up front gauging the interest of the community in your decision. Where it’s high, you need to commit to more than just your legislative bare-minimum consultation requirements.

Lesson #5: Low-tech cycleways might no longer be a viable solution

Cycleways have become more popular internationally and here in New Zealand. They are seen as having public health benefits, as well as reducing carbon emissions.

Safety is the main consideration when designing a cycleway. If you want cyclists to cruise along next to big trucks, you need to create a dedicated space to keep them safe.

The High Court judgment says “the Council’s aim to provide a cycling network suitable for all ages and abilities’ presents particular problems.” [para 13]

Children, inexperienced cyclists or less-abled cyclists may need a “solution that involves some form of separation from the main road carriageway.” [para 13] And you also have to provide a safe environment for pedestrians.

What does this mean for councils?

It means that if you intend to build a cycleway, you will most likely need to build a higher-tech version with a dedicated spaces for cyclists, vehicles and pedestrians.

If safety is the primary consideration, you will always be led down that path.

In other words, be careful about starting a cycleway project unless you are ready for that kind of investment.

Shifting from consultation to engagement

When talking about this in the office together, we were left with this question. “Do the minimum legal requirements for consultation dig deep enough?”

Yes, the Wellington City Council met the minimum legal requirements in this case.

But it took time for the Council to commit to the engagement process. The first rounds of consultation did not go deep enough to uncovering the community’s concerns and needs. There was no genuine two-way conversation with the community until the “Love the Bay” process, which was three years after the first consultation survey.

Consultation needs to dig deeper. Developments such as the new pilot programme for Local Democracy Reporters mean there will be an increased focus on council decision-making.

We also wondered: What was the financial cost of poor consultation here? At minimum, the redesign costed $4.1 million. But the costs probably exceeded that - in terms of the strained relationships and mistrust created throughout the project.

Is your organisation just doing the bare minimum consultation? Perhaps it’s time for a rethink.

P.S. Ngā mihi ki a Regan Dooley from http://www.islandbaycycleway.org.nz for informing us about factual mistakes in the original version of this article.

Dig deeper than bare-minimum consultation

Sometimes consultation doesn’t do enough for communities who want to be heard, involved and understood. But engagement processes are expensive and you can’t do it all the time. So how do you decide whether to invest in engagement?